Chapter Gallery of Images

Chapter Three:

Next Up for Owensboro and Daviess County: A New Narrative That Stokes the Fires of Innovation

by Keith Schneider

October 17, 2011

Confrontation In Two Arenas

In effect, Owensboro and Daviess County confront fierce contests in two arenas that require highly developed levels of definition and understanding. The first is external. Outside the country information technology, foreign competition, and terrorism have unnerved Americans. The nation’s customary feeling of command and control has been disrupted.

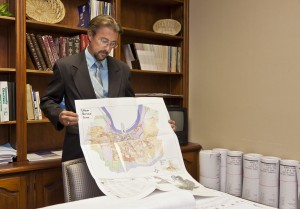

From 2006 to 2009, in new strategic plans and a well-attended community forum, Owensboro reached a striking consensus on the steps needed to forge a new path to prosperity. The most significant emphasized downtown redevelopment. Gary L. Noffsinger is the executive director of the Owensboro Metropolitan Planning Commission.

Taking its place inside the United States is a state of reaction that whipsaws between fear and thoughtless decisions that are eroding the country’s self-confidence. The nation’s two century-old democracy suddenly seems immature, and its leadership both ineffective and reckless.

The second confrontation is internal. From 2005 to 2011, Owensboro displayed a rare capacity to reach agreement on a downtown development plan and business retention strategy that was intelligent and practical. Unlike decisions in Washington and most states, the city and county reached compromises on investments that will ultimately prove to be more valuable than most residents believe is possible.

But Owensboro and the county, mindful of the 2010 election results, could easily retreat from the unity that the downtown development project represents. If it does, the city and county will quickly arrive at the same economic dead end of argument and grievance that has damaged so many other places in the United States. Paraphrasing New York Times journalist Tom Friedman, if Owensboro and Daviess County rein in their ambition, that could readily transform the few tough years that lie ahead for Owensboro into a bad century.

To be fair, it’s understandable that in the 2010 election Owensboro and Daviess County citizens and a good number of its elected officials exercised caution and seemed so ready to hug tightly to the old patterns and economic ideals of the 20th century. For a long time those tools worked. The prevailing market conditions shaped a popular national purpose, a big target of where to aim, and a clear picture of what economic success looked like.

That picture, which came to be known as the American Dream, was first introduced at the 1939 New York World’s Fair in the General Motors-sponsored Futurama exhibit. Futurama was a huge diorama of a highway-heavy, congestion-free, car-dependent, time-efficient, leafy green all-American suburban pattern of development that no one had ever seen before.

Chapter Video

Recommendations for More Success

- Undertake a New Community Strategic Plan – A new strategic planning initiative is needed to propel the city and county to the next stage of its progress as a center of opportunity.

- Cultivate and Recruit Women to Serve as Elected and Appointed Leaders – Almost 52 percent of Daviess County’s adults are women and that percentage is not reflected in elected positions in the city or county governments.

- Strengthen Internal and External Marketing and Communications – More focused outreach is vital to show citizens why a publicly-funded program of education, downtown development, and innovation makes sense in strengthening the economy over the next generation.

- Establish a Joint City-County Office of the Ombudsman – Thin out the cross-cutting permitting process while also providing the fairness and access that citizens expect.

- Establish and Fund the Owensboro Promise – Provide every graduate of the six Owensboro, Daviess County, and Catholic high schools scholarships for tuition and fees to attend a two- or four-year college in or outside Kentucky.

- Establish the Owensboro Top 20 Young Achievers Program – Provide the most talented young adults the chance to be part of Owensboro’s future and to stay connected.

- Foster Local Foods and Develop More Recreational Infrastructure – Healthier cities note their success as a marketing advan- tage in promotional campaigns.

- Generate More Diversity in Civic Life and Improve Business – Recruit investment and development capital from Asia, and especially from China.

- Promote New and Cleaner Energy Sources – Owensboro’s city-owned utility should serve as an innova- tor in carbon reduction technology, conservation, effi- ciency, solar development and other cutting edge thinking about energy production and consumption.

- Strengthen Transportation Hubs, Build a Streetcar Line – Owensboro’s opportunities over the next two decades are significant in air, ground, and river transportation.

- Put a Brake On Sprawl – Replace the love affair with big surface parking lots with a marriage to homes and businesses, recreation, and education infrastructure that is reachable on foot, on a bike, public transit, or a very short car ride.

- Promote Events and Bluegrass Music – Design and develop a new music center that houses the International Bluegrass Music Museum.